At the Palestinian Counseling Center (PCC), we encounter countless stories of pain, resilience, and recovery. Our work in mental health—especially with individuals facing depression—reveals how deeply emotional struggles can distort one’s perception of life, self-worth, and hope. This article, drawn from real therapeutic reflections (with pseudonyms used to protect identities), offers a compassionate exploration of what it means to live with depression and how the thought of “leaving” is often a desperate cry not to end life, but to end suffering.

Depression and the “Thought of Leaving”

You’re not alone in this...

Hussam Kanaaneh

Psychotherapist

Palestinian Counseling Center

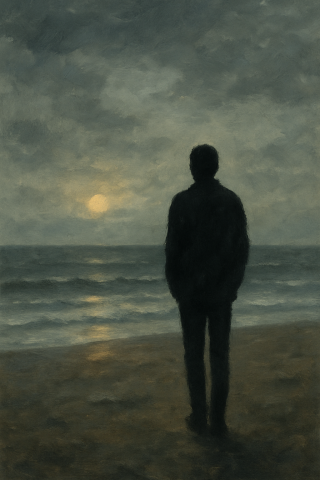

“Do you want to die? Throw yourself into the sea and you’ll find yourself fighting to live. You don’t want to kill yourself. You just want to kill something inside you.”

This popular quote circulating online is a reinterpretation of a line from the movie Cast Away (2000), where the character Chuck Noland (played by Tom Hanks) tells his friend:

“You don’t want to die. You just want the pain to go away.”

I often find myself revisiting these two quotes—both in therapy sessions and in quiet reflection—especially when working with individuals overwhelmed by depressive thoughts and a deep sense of despair. These words ring especially true for those experiencing what I call “thoughts of leaving”—when depression distorts thought patterns so severely that detachment from life itself feels like relief.

To begin, it's essential to understand that depression—particularly when hopelessness dominates—can feel like a complete collapse of meaning. In his 2001 book The Noonday Demon, Andrew Solomon describes depression not just as deep sadness, but as the total absence of feeling, something akin to psychological death. One woman, for instance, would respond at the end of each session, “I don’t know what I feel. I never did.”

Similarly, Lewis Wolpert, in Malignant Sadness (1999), compares depression not to normal sadness but to a malignant illness—like cancer—because of its power to devastate one’s physical and emotional life.

Take the example of Jamal, a man in his forties who has been unemployed for two years. He opens a session by saying:

“It’s not going well. Everything is hard.”

When asked what he finds difficult, he responds:

“The loneliness. It’s killing me. I go days without speaking to anyone. My body hurts. Life has no meaning. I’m distancing myself from everyone—even those closest to me. I’m scared. There’s a strange fear in me. I avoid people. I can’t study or look for work. I’m lost. This week was a disaster—like a tunnel with no end.”

Wolpert emphasizes that depression robs a person of the ability to enjoy anything—a reality echoed often in sessions by patients who say, “I don’t feel like doing anything.”

People with major depression often share feelings of helplessness, detachment from themselves, and a sense of alienation. One client, Nidal, a 26-year-old trainee lawyer, described his condition:

“I feel like something is sitting on my chest, stealing my breath. I’m wasting time just staring. I can’t interact with anyone. I don’t even want to talk to people.”

He continued,

“I can’t manage work. I feel like I’m falling apart. I don’t want to leave my room. I don’t want anyone to talk to me.”

Psychologist Aaron Beck (1967) defined depression as a mental disorder marked by deep sadness and a loss of interest in daily activities. In Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), before challenging automatic or distorted thoughts, we begin with behavioral activation—helping individuals re-engage with life and its simple routines.

As Judith Beck (2007) explains:

People often wait to feel better before doing something. But it’s doing something that helps them feel better.

I often use this metaphor: “Don’t wait until you have the appetite to cook your favorite meal—cook it, and the appetite may return.”

A simple task like “open a window” or “wash your face” can be a powerful first step out of inertia.

In his 1998 New Yorker article Anatomy of Melancholy, Solomon links depression to a mix of biological (neurochemical), psychological (trauma, loss), and social (isolation, poverty) factors. He also stresses the role of negative thinking patterns in deepening depression.

Aaron Beck’s “Cognitive Triad” explains that depression thrives on three interconnected components:

-

Negative thoughts about the self, the world, and the future

-

Depressed mood, including emotional numbness and fatigue

-

Withdrawal behavior, like social isolation and loss of motivation

These elements feed each other: the more one withdraws, the more isolated and hopeless they feel, leading to more negative thoughts. CBT seeks to break this cycle through:

-

Cognitive restructuring (e.g., “What’s the evidence that you’re a failure?”)

-

Behavioral activation

-

Mindfulness to regulate emotions

We often simplify this triad into what’s known as the “black triangle of depression”:

A dark view of self, others, and the future.

Returning to the therapy room—Maryam, in her thirties, said in her last session:

“Everything feels meaningless… I don’t know if I even want to come back to life.”

Jamal echoed a similar sentiment:

“Life is destruction. Everything looks black. I’m looking for a job but I don’t want to work. What am I even doing here? Nothing in this life is worth it.”

Aliya, 28 and unemployed, has lived with chronic depression since adolescence, including past suicide attempts. She described her week:

“Haven’t left the house in days. I’ve got no energy… But I’m still hanging on. I didn’t try to harm myself. I’m just endlessly bored. I didn’t even do the task you gave me. It’s all pointless. I see no future.”

When I asked why she still attends therapy, she replied:

“Honestly? I feel safe here. That’s why I keep coming.”

Her final comment reveals a critical truth:

She doesn’t see a future because she’s depressed—not the other way around.

The depression warps her thinking, fills her head with distorted beliefs, and convinces her that things will always remain dark.

Even Jamal’s claim that “there’s no reason to live” may not be his true belief—but depression speaking through him, clouding his vision. And Maryam’s experience may not reflect failure, but rather part of a non-linear healing process.

In times of collective crisis—like the current situation in Gaza—individual depression can be magnified by communal grief, further complicating recovery.

Therapy with depressed individuals is often filled with overwhelming emotions and exhausting thoughts. Many feel stuck in a hopeless spiral.

I often remind them:

“The thought of not wanting to live may be a symptom of depression—not a reflection of who you are.”

Depression tells people lies: that nothing will ever improve, that they are unworthy of love, that their pain is permanent.

But these are distortions—products of the illness, not of their truth.

So ask yourself:

If this heaviness disappeared right now, what would I do?

That answer may reveal that the desire to live is still there—just buried under the weight of exhaustion.

Let’s return to where we began:

“You don’t want to die. You just want to kill something inside you.”

So what is it that we’re trying to “kill”?

A wound we’ve carried too long?

A fear? A loss? A past that still whispers?

Whatever it is, it’s not permanent.

Because this, too—this storm, this pain, this confusion—will pass.

You're not alone in this.

Note:

-

All names have been changed.

-

This article does not replace individual psychological consultation or medical care.

Important References and Sources:

Solomon, A. (2024). "The Noonday Demon: An Anatomy of Depression" (translated by Omar Fathy). Assir Al-Kutub Publishing House.

Solomon, A. (2001). "The Noonday Demon: An Atlas of Depression" (translated by Abla Odeh). Abu Dhabi Tourism and Culture Authority.

Wolpert, L. (1999). Malignant sadness: The anatomy of depression. Faber & Faber.

Beck, J. (2007). "Cognitive Therapy: Foundations and Dimensions" (translated by Talat Matar). National Center for Translation.

Beck, J. S. (1995). Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond. The Guilford Press.

Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: clinical, experimental, and theoretical perspectives. Harper & Row.

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. International Universities Press.

Solomon, A. (1998, January 12). Anatomy of melancholy. The New Yorker, 46-61.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1998/01/12/anatomy-of-melancholy